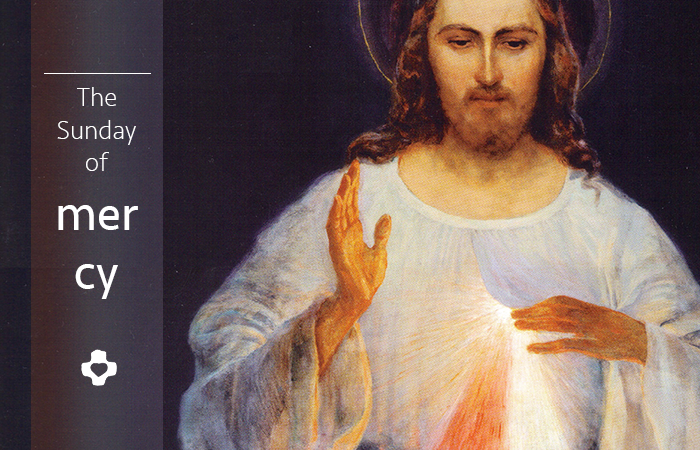

John Paul II wished that Whitsunday be celebrated as “Sunday of mercy.” This event gives us the opportunity to get closer to the gift that God does not tire of repeating. He shows himself a father of every believer, of every person, a father who calls to life, who educates and guides her children with faithful love. God rejoices when there is conversion, and the return of those who have gone astray.

In fact, however, it is easy to betray his will and to feel the bond with him as an unbearable constraint. To this failure is often added a terrible father image of God. To celebrate this festival means then to restore the correct image of God who sees conversion as the fruit of mercy, not of a retributive justice unknown to him. It is more important to understand that God loves us and that we ought to love God. Whoever does not act out of love feels like he or she is in prison; maybe, the person executes punctually all obligations, obeys the law, but perhaps does so only because he or she acts out of fear, feeling forced to do so.

Mercy comes only in the space of the freedom of love and of the gift. No wonder that the three decisive stages of the formation of the church, as attested in the Gospels, are marked by the remission of sins. The authority granted to Peter, as the bedrock of the ecclesial building, is essentially the power of forgiveness (Mt 16,19); the Eucharist, which gives shape to the entire ecclesial community, is the effective memory of the event in which Christ has shed his blood “for the forgiveness of sins” (Mt 26,28); the missionary mandate to the disciples enabled them to forgive sins (John 20,23). “He saved us, not because of any works of righteousness that we had done, but according to his mercy” (Tit 3,5).